OGGETTO-CAMPO Uno studio multi-risoluzione sull'ottimizzazione topologica - AGATHÓN

←

→

Trascrizione del contenuto della pagina

Se il tuo browser non visualizza correttamente la pagina, ti preghiamo di leggere il contenuto della pagina quaggiù

AGATHÓN – International Journal of Architecture, Art and Design | n. 07 | 2020 | pp. 144-153

ARCHITECTURE ISSN print: 2464-9309 – ISSN online: 2532-683X | doi.org/10.19229/2464-9309/7152020

RESEARCH & EXPERIMENTATION

OGGETTO-CAMPO

Uno studio multi-risoluzione sull’ottimizzazione

topologica

OBJECT-FIELD

The multi-resolution study of topological

optimization

Samuel Bernier-Lavigne

ABSTRACT

Con l’integrazione degli strumenti digitali nella progettazione architettonica, si può os-

servare una certa ridefinizione della nozione di ‘struttura’, lontana da schemi noti e ge-

neralmente studiati. Seguendo i progressi nei campi della simulazione e dell’ottimizza-

zione topologica, si esporranno alcuni progetti-chiave studiando il loro livello prestazio-

nale e delineando nella logica formale definita da questo processo il loro limite comu-

ne. Si ritiene che una possibile soluzione a questo limite risieda nel cambiamento di

scala nel metodo di progettazione, adottando sistemi a multi-risoluzione, in cui ogni

granello di materia può adattarsi alle informazioni strutturali presenti alla macro scala.

In considerazione di ciò, si propone un progetto di ricerca progettuale che esplora

questo salto di scala attraverso quattro oggetti-campo, ossia oggetti che sono formal-

mente autonomi, ma che tuttavia esprimono il loro campo strutturale interno attraver-

so una trasposizione a scala microscopica dell’ottimizzazione topologica.

Since the integration of digital tools into architectural design, we have observed a

certain reassessment of the notion of ‘structure’, taking us far from known and usual-

ly studied schemes. Following the advancement in simulation and topological opti-

mization, we will expose the key projects, study their level of performance, but also

underline a common limit: their formal logic defined by this process. We believe that a

solution to this limit lies in a change of scale in the design method, with multi-resolu-

tion systems, where each grain of matter can adapt to the structural information pre-

sent at the macro scale. Thus, we propose a design research project exploring this

game of scale through four object-fields, objects which are formally autonomous, but

nevertheless express their internal structural field with microscopic translation of

topological optimization.

KEYWORDS

oggetto-campo, multi-risoluzione, ottimizzazione topologica, progettazione algoritmica,

fabbricazione digitale

object-field, multi-resolution, topological optimization, algorithmic design, digital

fabrication

Samuel Bernier-Lavigne, PhD, is a Full Professor at Laval University’s School of Ar-

chitecture in Québec (Canada), and Founder of the FabLab-ÉAUL. He holds a Doc-

torate in Architecture (theory, design and digital fabrication), in addition to being a re-

cipient of the Henry Adams Medal of Honor (AIA), the RAIC Student Medal. He has

notably worked for Studio Cmmnwlth, Gramazio & Kohler (ETH), and UNStudio. E-

mail: samuel.bernier-lavigne@arc.ulaval.ca

144Bernier-Lavigne S. | AGATHÓN | n. 07 | 2020 | pp. 144-153

Prendiamo atto dell’evolversi di alcune no- alla struttura presa in esame (Bendsøe and pretare questo processo come la simulazione

zioni fondamentali dovute allo sviluppo tecno- Sigmund, 2003)2. Tecnicamente, il processo di digitale di un sistema materico dinamico che cer-

logico. I concetti di materia e materialità, che ottimizzazione topologica inizia con la definizio- ca di trovare il proprio equilibrio formale a ogni

assolvono in architettura principalmente la fun- ne di un volume o di una superficie da ottimiz- costo, usando alla fine la minore energia possi-

zione strutturale, sono tra quelli che sono de- zare, ossia il suo campo d’azione. Viene quindi bile per poter esistere.

stinati a cambiare, sia dal punto di vista forma- suddiviso in elementi discreti con caratteristi- A primo acchito è evidente una diretta cor-

le sia nei loro aspetti di fabbricazione. Come ri- che materiali predefinite, su cui viene eseguita relazione con il settore della progettazione per

levato da Antoine Picon (2018), la materialità un’analisi degli elementi finiti in sequenze cicli- la complessità geometrica risultante dall’otti-

dipende dagli utensili, dagli strumenti e dalle che (loop): l’obiettivo è far convergere la distri- mizzazione topologica, ma anche per i nume-

macchine che utilizziamo, tutti elementi fonda- buzione del materiale in percorsi ottimali (opti- rosi vincoli di produzione con cui si deve con-

mentali per determinare l’approccio alla scien- mal pahts) all’interno di un dato dominio, in frontare3. Se nel campo dell’industrial design

za, alla filosofia e all’architettura. Adesso questi modo da concentrare la materia solo dove ne- diversi sono i progetti che mirano a ottimizzare

utensili, questi strumenti e queste macchine cessario e rimuovere qualsiasi parte non es- la struttura – basti pensare alla Bone Chair di

sono digitali e ci permettono di esplorare forme senziale per la stabilità strutturale dell’insieme Joris Laarman (2017) oppure ai telai delle auto-

e strutture inedite, determinando anche una (Cazacu and Grama, 2014). È possibile inter- mobili – a livello architettonico rari sono i casi in

nuova comprensione dei fenomeni fisici che li

caratterizzano. Invece di allontanare l’architet-

tura dal mondo materiale, come molti avevano

erroneamente predetto, la tecnologia digitale

ha catalizzato una fase di transizione dalle tipo-

logie strutturali, intese come modelli usuali già

utilizzati dagli architetti, alle topologie struttura-

li, nuovi modelli che si sono rivelati improvvisa-

mente più fluidi e complessi dei precedenti.1

La libertà di progettazione così riconquista-

ta è favorita da strumenti matematici razionali

che sono in grado di creare simulazioni basate

sull’unione di informazioni formali, materiali e

strutturali. In particolare, i metodi di analisi sugli

elementi finiti (FEM) sono in grado di calcolare

con precisione la distribuzione dei carichi all’in-

terno di una forma, facilitando il controllo di

questi dati durante la fase di progettazione, ma

soprattutto, ci consentono di pensare la strut-

tura nel suo complesso, piuttosto che come

un insieme separato di elementi. L’ingegnere

giapponese Mutsuro Sasaki (2007) svilupperà

la teoria della ‘morphogenesis of flux struc-

tures’, dimostrando il suo metodo attraverso la

realizzazione di alcuni dei più importanti pro-

getti contemporanei giapponesi, come la strut-

tura autoportante a guscio di calcestruzzo del

Teshima Art Museum di Ryue Nishizawa (Vv.

Aa., 2017) e il Crematorio Meiso no Mori di

Toyo Ito (et alii, 2009), progetto nel quale è

possibile notare gli effetti che la distribuzione

continua delle forze ha nel determinare la su-

perficie ondulata della copertura con l’obiettivo

di renderla stabile e di minimizzare le sollecita-

zioni strutturali (Fig. 1). Stesso approccio è quel-

lo dell’ingegnere Cecil Balmond (2007), le cui

‘informal structures’ consentono l’esplorazione

di nuovi spazi architettonici, come nel caso

della Arnhem Station Transfer Hall di UNStudio

dove un’unica superficie strutturale comples-

sa è in grado di connettere la copertura, i sup-

porti verticali, le pareti, i collegamenti e gli oriz-

zontamenti tra i diversi livelli.

Ottimizzazione Topologica | L’evoluzione del

concetto di struttura come ‘flusso’, databile al

primo decennio dell’attuale secolo, ha portato

a una nuova lettura della distribuzione delle

sollecitazioni strutturali, assumendo queste ul-

time come fattore capace di generare risultati

ancora più prestazionali. Prendendo ispirazio-

ne da alcuni processi morfogenetici naturali

come le trabecole ossee, è stato messo a

punto uno strumento in grado di eliminare gra-

dualmente tutta la materia non strutturale, ana- Fig. 1 | Toyo Ito and Mutsuro Sasaki, ‘Meiso no Mori Crematorium’, Kakamigahara 2006 (credit: L. Smith, 2016).

lizzando iterativamente il flusso di forze interno Fig. 2 | Benjamin Dillenburger, topology optimization for a concrete slab, ETH Zurich 2016 (credit: B. Dillenburger, 2016).

145Bernier-Lavigne S. | AGATHÓN | n. 07 | 2020 | pp. 144-153

cui tale processo generativo che potrebbe ef- esplorare si basa sul concetto del ‘cambio di to consente infatti maggiore autonomia formale

fettivamente determinare importanti cambia- scala’, sia nei processi di progettazione sia di nella definizione dell’oggetto, sfruttando la com-

menti sia nella progettazione sia nella costru- materializzazione. Per ambire a un rinnova- plessità e la variabilità del campo, ma questa

zione, è stato applicato. Il più noto è il Qatar mento concettuale, in una prima fase di lavoro volta limitandolo all’interno dell’oggetto iniziale al

National Convention Center di Arata Isosaki: il occorre considerare il progetto come un tutto, fine di influenzare principalmente la sua materia-

Centro si caratterizza per la presenza di una un oggetto, concentrandosi quindi sull’ideazio- lità. Nel nostro caso il campo sarà composto dal-

struttura che, come un albero, emerge dal ter- ne. L’oggetto è considerato come autonomo e le linee di forza risultanti dall’ottimizzazione to-

reno e si dirama per sostenere la maestosa co- libero da tutti i vincoli abituali, e concepito co- pologica dell’oggetto progettato.

pertura (Sasaki, 2007). Nonostante le dimen- me spazio finito, come elemento materiale e

sioni dell’edificio, la struttura non rivela pratica- come ‘dispositivo affettivo’; al contempo, la Risoluzione | Sviluppando ulteriormente il di-

mente alcun processo di post-ottimizzazione o scala ridotta facilita la sua fabbricazione e aiuta scorso, la connessione tra oggetto e campo

di razionalizzazione, rendendo la sua costru- a validare rapidamente le qualità dell’oggetto può anche essere vista come una relazione tra

zione una sfida senza precedenti. finale. Questo approccio diventa effettivamente versioni a diversa risoluzione della stessa en-

Un altro caso di grande interesse per il mon- interessante quando si confronta l’oggetto iso- tità. Il primo è un elemento a bassa risoluzione,

do della ricerca architettonica è rappresentato lato con i flussi di forze che lo attraversano, i un semplice contenitore debolmente definito;

dal Topology Optimization for a Concrete Slab, quali diventano tutto d’un tratto il suo unico cam- l’altro è un sistema dinamico altamente diffe-

presso il Politecnico di Zurigo, progettato dal po vettoriale, l’espressione completa del suo renziato che contiene una notevole quantità di

Prof. Benjamin Dillenburger e dal suo team. ‘milieu energetico’ (von Uexkull, 2010). Questo informazioni. Questa lettura degli elementi è

Con l’obiettivo di ridurre il consumo di calce- approccio fa parte di un più ampio quadro teo- accentuata dall’ambiente digitale in cui sono

struzzo nel settore delle costruzioni, partendo rico, descritto in dettaglio in un precedente ar- creati e, come indica Mario Carpo (2014), dagli

da un solaio standard, il team ne ha ottimizza- ticolo, che traccia l’interazione tra due compo- strumenti che utilizziamo poiché inevitabilmen-

to la topologia, eliminando il 70% della materia nenti elementari nella breve storia dell’architet- te gli stessi si riflettono su ciò che produciamo.

non necessaria e massimizzandone al contem- tura digitale: l’oggetto e il campo (Bernier-Lavi- I modelli digitali con cui lavoriamo hanno una

po le prestazioni strutturali (Jipa et alii, 2016; gne, 2020). risoluzione al di sotto della nostra soglia di per-

Fig. 2). Tuttavia, la complessità geometrica del cezione (Young, 2018) – il ‘minimum separabi-

progetto ha richiesto, per la sua realizzazione, Interazione tra oggetto e campo | Agli albori le’ dell’occhio umano – ma sono ora in grado

un sistema di casseforme di sabbia stampate dell’architettura digitale, diversi approcci con- di gestire una quantità notevole di dati. Di con-

in 3D con la tecnologia VoxelJet; con lo stesso cettuali al progetto hanno portato allo sviluppo seguenza, sempre più dati possono essere ar-

sistema, il team ha sviluppato anche il suo ulti- di un ‘campo energetico’ (composto da forze chiviati in contenitori sempre più piccoli – o in

mo progetto, lo Smart Slab, realizzato durante che si attraggono e si respingono, reali o con- oggetti come in questo caso – rendendo deci-

la costruzione della DFAB House di Zurigo cettuali) con l’obiettivo di ricercare condizioni samente più interessante affrontare il tema del-

(Aghaei-Meibodi et alii, 2017). statiche lontane dal normale equilibrio (ossia l’alta risoluzione.

Nonostante il carattere d’innovazione pro- lontane dalle pratiche consolidate) attraverso un Mentre un progetto a bassa risoluzione re-

mosso da ciascuno dei progetti descritti e i dif- approccio del tipo bottom-up. Nella maggior sta alla macro o alla mesoscala, a seconda del-

ferenti approcci all’ottimizzazione topologica, è parte dei casi, il risultato architettonico è stato la natura del progetto, l’idea di alta risoluzione

possibile comunque individuarne un limite: i ri- meno importante della complessità del suo ci proietta nella micro o, addirittura, nella nano-

sultati geometrici sono tutti simili. Una spiega- processo generativo (Teyssot and Bernier-La- scala (Nakamura, 2010). E così ci si ritrova da-

zione è rintracciabile nel processo di materializ- vigne, 2011). Possiamo facilmente individuare vanti a nuovo territorio da esplorare, in cui pos-

zazione dei flussi alla base di questa procedura analogie con l’ottimizzazione topologica, consi- sibilità e complessità si moltiplicano, e dove

algoritmica: se tutto il materiale strutturalmente derando che, nonostante il suo funzionamento ogni granello di materia, ogni mattone elemen-

sottoutilizzato viene eliminato, tutto ciò che ri- e i suoi parametri siano piuttosto definiti, l’esito tare alla scala del micron, diventa improvvisa-

mane è una rete fluida e interconnessa di di- formale è in qualche modo al di fuori del nostro mente accessibile all’architetto (Carpo, 2016).

stribuzione dei carichi, dai punti di applicazione controllo. Successivamente, con l’ascesa del La consueta gerarchia tra le diverse scale del

fino ai supporti. Nell’insieme, tutti i progetti ‘parametrico’ – inteso sia come strumento sia progetto lascia il posto a una metodologia di

rappresentano un’evoluzione di quella ‘architet- come ‘architettura parametrica’ – i progettisti progettazione più flessibile, in grado di integra-

tura strutturale’ che trova la massima espres- digitali hanno potuto avere un migliore control- re scale variabili e parallele, in cui i minimi det-

sione negli anni ’50 e ’60 con il lavoro di Em- lo sul processo, restringendone in una certa tagli rafforzano il tutto e viceversa. In questa di-

merich, Le Ricolais, Wachsmann e Fuller (Wigley, misura la gamma di possibilità. mensione minima, il confine tra forma e mate-

2001); a differenza di allora, per facilitare la di- Il risultato di questa prima evoluzione con- ria diventa sfocato (Beckett and Babu, 2014),

stribuzione multidirezionale dei carichi, ora i cettuale è il ‘campo degli oggetti’, concetto sebbene sia importante notare che la transizio-

nodi strutturali vengono ‘levigati’ attraverso basato sul fatto che la moltiplicazione di un ne da un oggetto digitale al suo equivalente fi-

operazioni di ‘smoothing’, seguendo una rego- componente in grado di adattarsi alle variazioni sico porta inevitabilmente a una riduzione della

la simile alle condizioni del Plateau (Thompson, del campo mediante graduale differenziazione risoluzione.

2009) e ricordando alcune strutture naturali crea una molteplicità di oggetti simili e legger- Tutte queste alterazioni nella scala d’inter-

che molto hanno affascinato questi architetti. mente diversi. Rispetto a questa visione, la vento influenzano necessariamente il modo in

Ora, come possiamo aggirare i vincoli formali reazione di molti architetti è stata quella di di- cui analizziamo i progetti. Se, a un primo sguar-

inerenti l’ottimizzazione topologica, in modo che sconnettere l’oggetto dal campo (Gage, 2015) do, agli aspetti più superficiali delle cose rivela-

diventi uno strumento di progettazione aperto, e iniziare a esaminare le sue qualità nascoste no alcune informazioni, come i contorni facil-

anziché avere come finalità solo ciò che è pro- (Harman, 2013), quelle che, secondo Micheal mente comprensibili dell’oggetto, molto può

dotto da questo processo? Quali potrebbero Benedikt e Kory Bieg (2018), «[…] do[es] not ancora sfuggire alla nostra comprensione re-

essere le qualità spaziali, materiali e visive lega- disclose […] fully to each other [but] exist re- stando a questo livello di osservazione. È ne-

te all’ottimizzazione topologica, se allargassi- gardless of human regards» (Benedikt and Bieg, cessario decodificare il resto, strato per strato,

mo lo spettro della riflessione? 2018, p. 8). cambiando pertanto la nostra scala di analisi e

Alla luce di tutto ciò, la ricerca di seguito illu- modificando l’angolo d’osservazione, per svela-

Progetto | Il presente contributo illustra un strata propone di esplorare un nuovo, e proba- re infine il mistero degli altri livelli organizzativi

progetto di ricerca che tenta di ‘aggirare’ i limiti bilmente definitivo, legame tra l’oggetto e il del campo. Ovviamente, l’architettura non è la

discussi. Per fare ciò, occorre considerare il ri- campo – l’oggetto-campo – poiché sembra che prima disciplina che affronta gli effetti della riso-

sultato dell’ottimizzazione topologica come un queste due entità abbiano ancora alcune cose luzione multipla, come dimostrano le ricerche

diagramma capace di guidare, in modo creati- da offrirsi l’un l’altro e potrebbero ancora una nel campo della Fisica nel Novecento. I fisici

vo, un progetto concettuale (Teyssot, 2012). Il volta stimolare la riflessione su possibili scenari hanno infatti dimostrato che lo stesso fenome-

punto di partenza in questo nuovo campo da architettonici. Questo concetto di campo-ogget- no o oggetto può rivelare due aspetti completa-

146Bernier-Lavigne S. | AGATHÓN | n. 07 | 2020 | pp. 144-153

mente diversi a seconda della scala di analisi e

delle teorie ad esso associate: alla scala medio-

grande con la meccanica classica, e alla micro-

scala con la meccanica quantistica (Kumar,

2013). Comunque, ciò che è certo è che la vali-

dità di questi modelli di analisi è relativa alla

scala di applicazione (Bontems, 2008).

Tuttavia, scopriremo che, per poter mate-

rializzarsi, il campo utilizzerà diversi sistemi di

trasposizione dando corpo al contempo all’og-

getto. Questi sistemi potrebbero essere con-

frontati con un dispositivo di amplificazione,

ossia con uno strumento che consente la co-

municazione di microelementi con scale di os-

servazione più grandi (Simondon, 2012). La

reale comprensione di questi sistemi dovrà però

passare attraverso un’analisi rigorosa: innanzi-

tutto, partendo dalla macroscala, l’insieme do-

vrà mostrare la direzionalità delle linee di forza;

successivamente, passando alla mesoscala,

dovrà essere verrà messa in luce la logica di

assemblaggio locale, ponendo attenzione a

che l’abbondanza di informazioni digitali, al-

l’apparenza disordinate, non provochi una sen-

sazione di straniamento (Young and Young &

Ayata, 2015); infine, alla microscala, si potrà

passare a osservare in dettaglio i componenti

di base che appariranno però frammentati e

astratti. Questa logica risponde all’idea di ‘ordi-

ne di grandezza’ del filosofo Gilbert Simondon,

che suddivide un problema in diverse realtà

mediate dall’osservatore grazie a uno strumen-

to (Hui, 2016), individuato nel nostro caso in un

algoritmo che ci permette di realizzare un si-

stema di traduzione tra le diverse scale.

Pertanto, l’idea non è quella di limitarci a un

solo aspetto di queste diverse risoluzioni igno-

rando le altre, obbligandoci a scegliere tra l’alta

o la bassa risoluzione, ma piuttosto di sfruttare

l’intero spettro secondo la logica dei frattali. È

attraverso queste variazioni di scala, il salto

inatteso dal nulla al nulla, in cui realizziamo che

qualcosa sta effettivamente accadendo e dun-

que prestiamo attenzione (Gage and Meredith,

2019). Ciò è esattamente quanto si illustrerà

nei quattro ‘oggetti-campo’ che seguono, dove

l’accesso a nuove scale di progettazione po-

trebbe forse rinnovare la nostra comprensione

della realtà architettonica.

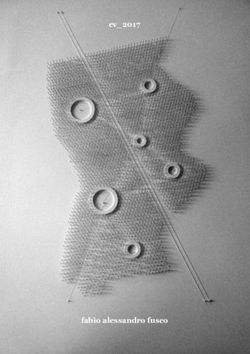

Oggetti-campo | La ricerca progettuale sul-

l’oggetto-campo mira a esplorare i tratti carat-

teristici di un processo di ottimizzazione topolo-

gica ad alta risoluzione vincolato però in un vo-

lume predefinito di risoluzione inferiore. Da qui

una riflessione sull’oggetto base, quello che in-

fine ospiterà il campo. Per garantire una certa

coerenza nella generazione dell’oggetto base, il

suo design parte da un volume di 150 x 150 x

300 mm su cui viene eseguito lo stesso tipo di

operazione, ossia una differenza booleana defi-

nita da due parametri iniziali e con diverse itera-

zioni possibili. Tale operazione determina la per-

centuale massima del volume di ciascuna sot-

trazione e il numero d’iterazioni da eseguire.

Man mano che le operazioni booleane vengono

generate casualmente, emergono una serie di

monoliti finemente tagliati, con caratteristiche

simili sebbene formalmente diversi (Fig. 3). Se- Figg. 3-5 | Monolithic objects: algorithmic process with random Boolean operations; classification and selection; 3d print

condo Marie-Ange Brayer (et alii, 2010), l’a- of the four selected objects (credits: S. Bernier-Lavigne, 2020).

spetto interessante dell’oggetto come monolite Fig. 6 | Structural flow extracted from the topological optimization of the objects (credit: S. Bernier-Lavigne, 2020).

147Bernier-Lavigne S. | AGATHÓN | n. 07 | 2020 | pp. 144-153

voxel ottiene la propria colorazione (Figg. 7, 9).

Il terzo oggetto-campo mira a una comple-

ta integrazione dei flussi strutturali attraverso la

creazione di un monolite trasparente, semplice

all’esterno ma estremamente dettagliato all’in-

terno. Poiché l’interno dell’oggetto è vuoto,

l’ottimizzazione topologica è intrinsecamente

incorporata nel suo involucro, come se queste

informazioni si fossero gradualmente dissolte

durante il processo di progettazione e poi fos-

sero riapparse durante la sua materializzazio-

ne. A questo punto un algoritmo di sposta-

mento dei vertici viene utilizzato per ispessire

parti delle pareti interne del monolite, conferen-

dogli una trama che, seguendo la direzione

delle forze, risulti finemente increspata ma

fluida al tempo stesso. Realizzato attraverso

stampa 3D in resina ultra trasparente con strati

di 15 micron, questo oggetto-campo appare

come un’entità ottenuta attraverso un proces-

so di crescita piuttosto che di fabbricazione,

dal quale prende corpo un intenso ma delicato

dialogo tra la spigolosità dei bordi del profilo

esterno del monolite e la sottile variazione della

superficie interna, che porta ad affascinanti ef-

fetti ottici se osservati da vicino o attraverso la

luce naturale (Figg. 7, 10).

Con il quarto e ultimo oggetto-campo sia i

dati formali del monolite iniziale che i flussi

strutturali vengono decomposti, in modo da

sfumare completamente i confini tra oggetto e

campo, attraverso il principio dell’assemblaggio

mereologico (Bryant, 2011) di semplici elementi

lineari i quali, nonostante misurino solo pochi

micron, riescono a sviluppare una stretta rela-

zione con il tutto. La procedura algoritmica divi-

de la forma iniziale in una serie di sottili elementi

Fig. 7 | The four object-fields (credit: S. Bernier-Lavigne, 2020). verticali ed estrae lo strato esterno dell’ogget-

to; contemporaneamente un ciclo iterativo vie-

ne eseguito diverse migliaia di volte per orga-

nizzare gradualmente i microelementi orizzon-

è che ne rinnega i presupposti legati all’estetica gli oggetti-campo, mentre quelli a quota supe- tali secondo i dati di ottimizzazione, mentre il

e al formalismo ma allo stesso tempo è inteso riore diventano quasi delle semplici linee. Il ca- tutto lentamente si solidifica. Il risultato mostra

come uno spazio privilegiato per la sperimenta- ratteristico aspetto dell’oggetto ad alta risolu- un oggetto-campo con un certo livello di elasti-

zione architettonica. Quattro di questi oggetti zione si rivela quando si tocca l’oggetto stam- cità, principalmente nelle sue aree meno stres-

sono stati selezionati in base alle qualità mo- pato, dove una trama sottile quasi invisibile a sate strutturalmente. La sua materializzazione

strate e al loro potenziale progettuale e sono occhio nudo, ma percepibile al tatto, rivela l’al- in resina traslucida, che restituisce un gioco co-

stati analizzati per l’ottimizzazione topologica tro tema progettuale (Figg. 7, 8). stante di pieni e vuoti a seconda dell’angolo e

(Figg. 4, 5). In sostanza è necessario estrarre i Il secondo oggetto-campo esprime i flussi della scala di osservazione, diventa in qualche

loro campi interni, l’effetto delle forze esterne strutturali come una fonte di informazioni per modo immateriale, simile ad alcune formazioni

sul volume fino ai supporti, e comprendere l’in- definire la superficie esterna del monolite. Que- nuvolose oniriche (Damisch, 1972; Figg. 7, 11).

fluenza che la geometria dell’oggetto ha su sta volta, il sistema ad alta risoluzione diventa Ognuno di questi quattro oggetti-campo

questo processo (Fig. 6). Da questo momento essenziale nella definizione del progetto, in cui poggia su una base, un pesante blocco che

in poi vengono sviluppati quattro sistemi ad alta un algoritmo decompone il volume totale in un controbilancia idealmente la leggerezza del-

risoluzione per trasformare i monoliti e i loro cluster di voxel da 1 mm, ossia in una sorta di l’oggetto posto su di esso. Sebbene comple-

flussi strutturali in oggetti-campo. pixel tridimensionali. Quindi, questa raccolta di tamente bianco come fosse un volume astrat-

Il primo sistema rappresenta una sorta di in- voxel è informata dai flussi dell’ottimizzazione to, la sua superficie superiore è fresata per

troduzione all’intero progetto, materializzando topologica, estrudendo i voxel secondo le nor- esprimere l’intensità del campo che agisce sul-

in modo quasi identico il risultato dell’ottimizza- mali del volume iniziale. Ciò permette di irrigidi- l’oggetto, reinterpretando, a un’altra risoluzio-

zione. Troviamo, naturalmente, come output ti- re la struttura dove è necessario, aumentando ne, il sistema di traduzione utilizzato. D’altra

pico di questo processo una mesh fluida, che in queste aree la quantità di materia. Sull’og- parte, questa nozione di multi-risoluzione ha

ci fornisce la chiave di volta per la comprensio- getto viene poi generata una topografia pixella- grandi ripercussioni quando arriva il momento

ne degli altri tre oggetti-campo. Inoltre, l’output ta e, per amplificare queste sottili variazioni, di rappresentare il progetto (Allen and Caspar

esprime anche la qualità spaziale della mesh vengono assegnate sfumature di grigio ai voxel Pearson, 2016). Abbiamo deliberatamente li-

che si evolve nel corpo dell’oggetto. In alcuni in base alla loro vicinanza al campo sottostan- mitato la nostra indagine ai disegni al tratto al

punti si può percepire ciò che resta dei limiti te. Ne consegue un rumore visivo altamente fine di esplorare la flessibilità di questo mezzo

spigolosi del volume iniziale, mentre in altre zo- differenziato che sembra quasi casuale se os- e capire se questo sistema di rappresenta-

ne i contorni sembrano svanire completamen- servato da vicino ma che risulta essere altamen- zione potesse essere utilizzato. Al di là delle

te. È possibile notare anche la differente distri- te indicativo nel suo insieme. Un processo di tecniche di base, sebbene sempre importan-

buzione del materiale: gli elementi strutturali più stampa 3D composto da polvere di gesso, le- ti, per ogni oggetto-campo viene sviluppata

vicini alla base si inspessiscono per stabilizzare gante e inchiostro produce l’oggetto, in cui ogni una procedura algoritmica, derivante dalle pe-

148Bernier-Lavigne S. | AGATHÓN | n. 07 | 2020 | pp. 144-153

culiarità della sua complessa geometria (Fig. 12).

La sovrapposizione delle ‘contour lines’ in

più direzioni crea una tensione tra la trama di li-

nee e lo ‘shader’ superficiale nella rappresen-

tazione del primo oggetto-campo. Una tecnica

simile viene utilizzata anche nel disegno delle

basi. Per il secondo oggetto-campo, ogni voxel

viene scomposto verticalmente in un numero

variabile di livelli, in base all’intensità del suo

colore, al fine di ricreare artificialmente il gra-

diente. Ancora una volta, la vicinanza con cui

analizziamo il disegno ci fa percepire informa-

zioni diverse. Da lontano, si potrebbe facilmen-

te confondere il disegno con un rendering ge-

nerato da un computer poiché la sovrapposi-

zione di linee le rende indistinte, ma da vicino si

riscontra tutta la ricchezza dell’alta risoluzione

attraverso la leggibilità di un numero quasi infi-

nito di segmenti verticali (Fig. 13).

Per il terzo e il quarto oggetto-campo, l’o-

biettivo è quello di rappresentarne la traslu-

cenza usando solo punti e linee; a tale scopo

viene generata una nuvola di punti estrema-

mente densa racchiusa in una serie di linee

nette che segnano i contorni esterni dell’og-

getto (Figg. 14, 15). Per l’ultimo, giocare con il

grado di opacità delle linee mette in evidenza il

flusso di forze che abitano l’oggetto. Tutto

sommato, l’uso di disegni al tratto e le relative

esplorazioni algoritmiche consentono l’espres-

sione libera e specifica per ogni oggetto-cam-

po, catalizzando una certa coerenza nella ri-

cerca progettuale in cui le somiglianze iniziano

a dialogare nonostante siano separate da mol-

teplici materialità.

Conclusioni | La ricerca presentata dimostra

l’importanza di affrontare i problemi di definizio-

ne della risoluzione e della scala nella progetta-

zione architettonica e in ambito teorico. Isolan-

do uno degli elementi, ad esempio i flussi strut-

turali espressi dal processo di ottimizzazione

topologica, e sviluppandolo in diversi modi con

sistemi ad alta risoluzione, è possibile acquisire

una migliore comprensione del loro specifico

potenziale attraverso una serie di aspetti certa-

mente non trascurabili: la tattilità del materiale

stampato, la rappresentazione grafica tridimen-

sionale del comportamento fisico all’interno

dell’oggetto, la tensione generata tra opacità e

trasparenza, la sottile dematerializzazione della

struttura e, oltre a tutto ciò, l’opportunità di ri-

pensare la rappresentazione del progetto.

Il prossimo passo sarà convertire questo

metodo per l’architettura, superando la speri-

mentazione su casi isolati e considerando tutti

i vincoli che entrano nel processo di progetta-

zione. Con l’aumentare della dimensione del

progetto, le scale intermedie si moltiplicheran-

no sicuramente, rendendo necessario allarga-

re la terna scalare micro/meso/macro a ulte-

riori livelli di scale intermedie. Sarà necessario

implementare la multi-risoluzione in modo da Fig. 8 | Object-field #1, close-up on the tactile element

creare una vera complessità su scala variabile, of the 3d print (credit: S. Bernier-Lavigne, 2020).

attraverso l’eterogeneo intreccio di differenti li- Fig. 9 | Object-field #2, close-up on the visual noise of

velli di informazioni. the voxel system (credit: S. Bernier-Lavigne, 2020).

Fig. 10 | Object-field #3, close-up on the dialogue be-

tween the exterior and interior surfaces (credit: S. Bernier-

Lavigne, 2020).

It is normal to see certain fundamental notions Fig. 11 | Object-field #4, close-up on the mereological

evolve as a result of technological development. system (credit: S. Bernier-Lavigne, 2020).

149Bernier-Lavigne S. | AGATHÓN | n. 07 | 2020 | pp. 144-153

Rather than pushing away architecture from rations of American car companies trying to re-

the material world as many have wrongly an- duce the weight of their chassis. However, at

ticipated, digital technology has catalyzed a the scale of architecture, where this generative

transition from structural typologies, the typi- process could actually signify important

cal models used by architects, to structural changes both in design and construction, there

topologies which are suddenly more fluid and are very few examples of applications. The

complex.1 most well-known is the Qatar National Con-

Behind this regained freedom in design lies vention Center from Arata Isosaki, where like a

rational mathematical means, which are able to tree, the structure emerges from the ground

merge formal, material and structural informa- and branches out to support the gigantic roof

tion, through simulation. Thus, finite element at arm’s length (Sasaki, 2007). Despite the size

analysis methods are able to precisely calcu- of the building, the structure demonstrates vir-

late the load distribution inside a shape, and tually no post-optimization differentiation or ra-

facilitates the control of this data during the de- tionalization, making its construction an un-

sign phase. But more importantly, it leads us precedented challenge.

to think of structure as a continuous mixture Otherwise, a case of great interest in the

rather than a separate set of blocks. The architectural research world can be found in

Japanese engineer Mutsuro Sasaki (2007) will the project Topology Optimization for a Con-

develop the theory of ‘morphogenesis of flux crete Slab at ETH Zurich by Professor Ben-

structures’, demonstrating his method by real- jamin Dillenburger and his team. Aiming to re-

izing some of the most important contempo- duce the consumption of concrete in the con-

rary Nippon’s projects, such as the self-sup- struction industry, they use topological opti-

porting concrete shell of the Teshima Art Mu- mization to reduce the mass of an initial do-

seum by Ryue Nishizawa (Vv. Aa., 2017) and main – the standard slab – and manage to

the Meiso no Mori Crematorium by Toyo Ito (et eliminate 70% of it, while maximizing its struc-

alii, 2009). We see, in this last project, the ef- tural performance (Jipa et alii, 2016; Fig. 2).

fect of continuous distribution of forces in the However, the geometric intrication of the pro-

roof surface that undulates in order to stabilize ject is such that they had to develop a 3d

and minimize its structural stress (Fig. 1). A printed formwork system in sand, with the

similar approach with the engineer Cecil Bal- VoxelJet technology, to be able to realize it.

mond (2007) and his ‘informal structures’, which This will set the stage for their latest project,

allow complex geometries, such as UNStu- the Smart Slab, which was carried out during

dio’s Arnhem Station Transfer Hall, to connect the construction of the DFAB House in Zurich

the roof, columns, walls, circulation and floor in- (Aghaei-Meibodi et alii, 2017).

to a single structural surface, enabling the ex- Despite the innovative aspect of all these

ploration of new architectural spaces. projects and their distinct approaches to topo-

logical optimization, a certain limit appears to

Topological optimization | From this under- impose itself: their geometric results are all

standing of structure as flow, mainly developed similar. This can be explained by the material-

in the first decade of the 21st century, will ization process of flows, underlying this algo-

emerge a desire to channel the stress distribu- rithmic procedure. If all the structurally under-

tion in order to generate results of even greater utilized material is eliminated, all that remains

performance. Inspired by certain natural mor- is the fluid and interconnected network of load

phogenetic processes like the trabecular bones, distribution from its sources to its supports. It

a tool will allow this ideal to be achieved by is in fact a more specific and differentiated

iteratively analyzing the flow of forces and version of the structural network architecture,

gradually eliminating all non-structural matter at its peak in the 1950s-60s with the work of

(Bendsøe and Sigmund, 2003)2. Technically, Emmerich, Le Ricolais, Wachsmann and Fuller

the topological optimization process starts with (Wigley, 2001). This time, to facilitate the mul-

the definition of a volume or surface to be op- ti-directional distribution of loads, the struc-

timized; its field of action. It is then subdivided tural nodes are smoothed, following a similar

into discrete elements with predefined materi- rule to Plateau’s conditions (Thompson, 2009),

Fig. 12 | The four object-fields, elevation drawings (cred- al characteristics, on which a finite element and reminds us of certain natural structures,

it: S. Bernier-Lavigne, 2020). analysis is performed in loops. The goal is to an absolute fascination for these architects.

Fig. 13 | Object-field #2, close-up high-resolution draw- make the material distribution converge in op- From there, how can we get around this formal

ing (credit: S. Bernier-Lavigne, 2020). timal paths within this domain, and reduce the constraint inherent to this operation, so that it

mass of the structure by removing any materi- would become an open design tool, rather

al that is not essential to the structural stability than imposing its output as a finality? What

Matter and materiality, whose one of the main of the whole (Cazacu and Grama, 2014). One could eventually be the spatial, material and

architectural function is structure, are among could also interpret this process as the digital graphic qualities related to topological opti-

those that are bound to change, both in their simulation of a dynamic material system, which mization, if we broaden the spectrum of re-

form and their fabrication. «[…] Materiality de- tries to find its formal equilibrium at all costs, flection?

pends on our tools, instruments and machines. while using in the end as little energy as possi-

These are fundamental to our scientific [,] ble to exist. Project | We propose in this paper, a design-

philosophical» and architectural approach- At first glance, a direct affiliation seems log- research project attempting this circumvention.

es, as Antoine Picon (2018, p. 64) mentions. ical with the field of design, due to the geomet- To do this, we will need to consider the result

These tools, instruments and machines are ric complexity resulting from the topological of the topological optimization as a diagram

now digital, and this opens up a field of possi- optimization, as well as the fabrication con- that would inform, in a creative way, a concep-

bilities for the exploration of forms and struc- straints that this creates3. We have seen some tual project (Teyssot, 2012). Our entry path in-

tures, but it also brings a new understanding of projects stand out, such as Joris Laarman’s to this new territory of exploration will follow

the physical phenomena that inhabit them. Bone Chair (Laarman, 2017) and the explo- the idea of the change of scale, both in the de-

150Bernier-Lavigne S. | AGATHÓN | n. 07 | 2020 | pp. 144-153

sign and the materialization processes. To be- Resolution | As we develop a bit further the 2012). Our genuine understanding of these sys-

gin, a first transition leads us to consider the thinking, this connection between object and tems will need to pass through a rigorous anal-

project at the scale of the object, where it be- field can also be seen as a relationship be- ysis. First, at the macro scale, the directionality

comes a medium to work mainly on the idea, tween different resolutions of the same entity. of the lines of force will be globally visible, then

wishing a conceptual renewal. This object is One is a low-resolution element, a simple and will be its local assembly logic at the meso

approached here as being autonomous, and sparsely defined container, the other is a scale, where an abundance of digital informa-

freeing itself from all usual constraints. The highly differentiated dynamic system holding tion, on the verge of disorder, causes a feeling

idea is to focus on the object as a finite space, an immense amount of information. All this is of estrangement (Young and Young & Ayata,

as a material element, and as an affective ma- accentuated by the digital environment in 2015), and finally a precise look at its basic

chine, in the deleuzian sense of them. More- which they are created, and as Mario Carpo components appearing fragmented and ab-

over, this small scale will facilitate its fabrication (2014) indicates, the tools we use inevitably stract at the micro scale. This echoes the ‘or-

and helps to quickly validate the qualities of a reflect on the things we produce. The digital der of magnitude’ in the work of the philoso-

monolithic object. This actually becomes inter- models we work with have a resolution below pher Gilbert Simondon, which «[…] divides the

esting when one confronts this isolated object our perception threshold (Young, 2018), the question into different realities as mediated to

with the structural flows that run through it, ‘minimum separabile’ of the human eye, and the observer by the instrument» (Hui, 2016, p.

which suddenly become its only force field, the are now able to handle a phenomenal quanti- 30), here the algorithm leading to the transla-

complete expression of its ‘energetic milieu’ ty of data. As a result, more and more data tion system.

(von Uexkull, 2010). This approach is part of a can be stored in smaller and smaller contain- Therefore, the idea is not to restrict our-

broader theoretical framework, detailed in a ers – or objects in this case – which drastical- selves to only one aspect of these resolutions

previous paper, which traces the interaction ly increases the interest in addressing the while ignoring the others, so there is no ques-

between two elementary constituents in the theme of high resolution. tion of choosing between high or low resolu-

brief history of digital architecture, namely the While a low-resolution design keeps us in tion, but rather to exploit the entire spectrum

object and the field (Bernier-Lavigne, 2020). the macro scale, or meso (intermediate scale) like the fractal logic would allow. It is through

depending on the project, the idea of high res- these variations in scale, the unexpected jump

Interaction between object and field | More olution plunges us into the micro or even nano from all to nothing, where we realize something

often than not in the early days of digital archi- scales (Nakamura, 2010). Thus, everything is is actually happening and we pay attention

tecture, the conceptual approaches of the pro- multiplied, the possibilities as well as the com- (Gage and Meredith, 2019). This is exactly

ject led to the development of an ‘energy field’ plexity, and a new territory of exploration opens

(made up of attractive and repulsive forces, real up where each grain of matter, each elemen-

or conceptual) in which the search for certain tary brick on the scale of the micron, suddenly

states far from the normal equilibrium was tar- becomes accessible to the architect (Carpo,

geted, leading to the emergence of bottom-up 2016). The usual hierarchy of scales gives way

projects. In the majority of cases, the architec- to a more flexible design methodology, capa-

tural result was less important than the intricacy ble of integrating variable and parallel levels,

of its generative process (Teyssot and Bernier- where the smallest details reinforce the whole

Lavigne, 2011). A certain parallel is immediately and vis versa. At this minimal dimension, the

drawn with topological optimization, whereas boundary between form and matter becomes

its operation and parameters are highly regulat- blurred (Beckett and Babu, 2014), although it

ed, but its formal result is somehow beyond our is important to note that a transition from a

control. Then came the rise of the parametric – digital object to its physical equivalent invari-

both the tool and the architecture – where the ably leads to a decrease in resolution.

digital designers were trying to obtain better All these alterations in the scale of interven-

control on the field, by constraining it within a tion necessarily influence the way we analyze

certain range of possibilities. projects. While a first look at the surface re-

The result will be the field of objects, since veals certain information, like the easily under-

the multiplication of a component capable of standable outlines of the object, a lot still es-

adapting itself to variations in the field, by grad- capes our grasp at this moment. We must de-

ual differentiation, creates a multiplicity of ob- code the rest, layer by layer, by changing our

jects that are both similar and vaguely different. scale of analysis and modifying our angle of at-

The reaction of many architects to the transfor- tack, to finally unravel the mystery of the other

mation of this method into a universal style, organizational levels of the field. Obviously, ar-

was to disconnect the object from the field chitecture is not the first discipline facing the

(Gage, 2015), and start examining its own hid- effects of multiple resolution, as demonstrated

den qualities (Harman, 2013), those that it «[…] by the break in scale that appears in 20th cen-

do[es] not disclose […] fully to each other [but] tury physics. They learned that the same phe-

exist regardless of human regards» (Benedikt nomenon or object can reveal two completely

and Bieg, 2018, p. 8). different aspects depending on the scale of

In light of all this, we suggest exploring a analysis and the theories associated with it,

new, and probably final link between the object whether at the medium or large scale, with

and the field – the object-field – since it seems classical mechanics, or at the micro scale with

that these two entities still have some things to quantum mechanics (Kumar, 2013). However,

offer each other, and could once again stimu- the direct consequence is that the validity of

late reflection on possible architectures. This these analysis scheme becomes relative main-

concept of the object-field thus allows a formal ly to the scale of application (Bontems, 2008).

autonomy in the definition of the object, while Nevertheless, we will discover that, in order

taking advantage of the complexity and variabil- to materialize, the field will use different sys-

ity of the field, but this time constraining it within tems of transposition giving body to the object

the initial object in order to influence mainly its at the same time. These systems could be

materiality. In our case, the field will be com- compared to an amplification device, an instru-

posed of the lines of force resulting from the ment that allows the communication of smaller Figg. 14, 15 | Object-field #3: plan and relation to the

topological optimization of the designed object. micro-elements at larger scales (Simondon, base; point cloud (credits: S. Bernier-Lavigne, 2020).

151Bernier-Lavigne S. | AGATHÓN | n. 07 | 2020 | pp. 144-153

what we will pursue in our four object-fields mization, to extrude themselves following the translation. On the other hand, this notion of

that follows, where access to new scales of normals of the initial volume. This has the ef- multi-resolution has great repercussions when

design may eventually renew our understand- fect of stiffening the structure where it is need- the time comes to represent the project (Allen

ing of architectural reality. ed, by increasing the amount of matter in and Caspar Pearson, 2016). We have deliber-

these areas. As a result, a pixelated topogra- ately restricted our investigation to line draw-

Object-field | This design-research project of phy is generated on the object, and to amplify ings in order to explore the flexibility of this

the object-field aims to explore the high-resolu- these fine variations, shades of grey are as- medium, to see if it could speak this language.

tion features related to topological optimization, signed to the voxels according to their proximi- Beyond the basic techniques, although always

constrained this time in a predefined volume of ty to the underlying field. Consequently, it important, for each object-field an algorithmic

a lower resolution. Here begins the reflection on emerges a highly differentiated visual noise procedure is developed, deriving from the pe-

the basic object, the one that will eventually that seem almost random when observed culiarities of its complex geometry (Fig. 12).

host the field. To ensure consistency in this se- closely, but turns out to be highly indicative as The overlay of contour lines following multi-

ries, the design starts with a volume of 150 x a whole. A 3d printing process made of plaster ple directions create a tension between line

150 x 300 mm on which the same Boolean dif- powder, binder and ink is used to materialize drawing and surface shader in the representa-

ference operation is executed with many itera- the whole, where each voxel gets its own tint tion of the first object-field. A similar technique

tions, according to two parameters initially de- from this fabrication method (Figg. 7, 9). is also used in the drawing of the bases. For

fined. They determine the maximum percent- The third object-field aims at a complete in- the second one, each voxel is vertically de-

age of the volume of each subtraction, and the tegration of the structural flows through a composed into a variable number of lines,

number of iterations to be performed. As the transparent monolith, plain from the outside, based on the intensity its color, in order to arti-

positioning of these Boolean operations is ran- but extremely detailed from the inside. Since ficially recreate the gradient. Once again, the

domly generated, a series of finely cut mono- this one is empty, the topological optimization proximity at which we analyze the drawing

liths emerges, with similar characteristics al- is immanently embedded in its envelope, as if makes us perceive different information. From

though formally different (Fig. 3). this information had gradually dissolved during afar, one could easily mistake the drawing for

The interesting aspect of the object as a the design process and then reappeared in its a computer-generated rendering, where the

monolith is that it presents itself as «[…] a refu- materialization. Here, a vertex displacement al- accumulation of lines becomes practically

tation of all aesthetic presuppositions as well as gorithm is used to thicken parts of the inner opaque, but up close one finds all the richness

of all formalism» but at the same time it is walls of the monolith, giving it a texture that is of high resolution in this quasi-infinite number

meant to be a «privileged space for architec- both crackling and fluid, following the direction of vertical segments (Fig. 13).

tural experimentation» (Brayer et alii, 2010, p. of the forces. Fabricated with ultra-clear resin For the third and fourth object-fields, the

7). Four of them are selected, according to the 3d print exhibiting the accuracy of 15 microns goal is to represent their translucency using

qualities exhibited and their potential to be de- per layer, this object-field could almost be ap- only points and lines. Thus, the generation of

veloped in a project, and are analyzed by means prehended as an entity that would have been an extremely dense point cloud enclosed in a

of topological optimization (Figg. 4, 5). It is a formed by a growth process rather than manu- set of sharp lines marking the outer contours

matter of extracting their internal fields, the re- factured. A strong, though subtle, dialogue is of the object achieves this for one of them

sult of the external forces on the volume dis- established between the angularity of the (Figg. 14, 15). For the other, playing with the

tributed down to the supports, and under- sharp edges on the outside of the monolith degree of opacity of the lines brings out the

standing the influence of the geometry of the and the fine variation on the interior surface, flow of forces inhabiting the object. All in all,

object in this process (Fig. 6). From this point leading to fascinating optical effects when ob- the use of line drawings and the associated al-

on, four high-resolution systems are devel- served closely or in interaction with natural light gorithmic explorations allow the free and spe-

oped to transform the monoliths and their struc- (Figg. 7, 10). cific expression of each object-fields, in addi-

tural flows into object-fields. The fourth and final object-field decompos- tion to catalyze coherence throughout the pro-

The first one serves as a kind of introduc- es both the formal data of the initial monolith ject, where similarities, hitherto kept apart by

tion to the whole project, materializing close to and the structural flows, to completely blur the the multiple materialities, begin to dialogue.

identical the result of the optimization. We find, boundaries between object and field. This is

of course, this fluid mesh, the typical output of done through the mereological assembly (Bryant, Conclusions | This project demonstrates the

this process, giving the keystone to understand 2011) of simple linear elements, and although relevance of addressing issues of resolution

the other three object-fields. Moreover, it also these elements measure only a few microns, and scale in architectural design and theory. By

expresses the spatial qualities of this network they manage to develop a close relationship isolating an element, here the structural flows

that evolves into the body of the object. One with the whole. The algorithmic procedure di- emerging from topological optimization, and

comes to perceive, according to certain points vides the initial shape into a series of thin verti- developing it in multiple ways with high-resolu-

of view, what remains of the straight limits of cal members, extracting the periphery of the tion systems, allows a better understanding of

the initial volume, while at other times they have object, and an iterative loop run several thou- its specific potential. Many qualities can be

completely evaporated. Material gradation is al- sand times to gradually organizes the horizon- withdrawn: the tactility of the printed material,

so present; the structural members approach- tal micro-elements according to the optimiza- the three-dimensional graphic expression of the

ing the base thickens to stabilize the object- tion data, slowly solidifying the whole. The re- physical behavior inside the object, the genera-

field, compared to the more aerial ones that are sult shows an object-field with a certain level of tion of tension between opacity and trans-

on the verge of becoming simple lines again. elasticity, mainly in his less structurally stressed parency, the fine dematerialisation of the struc-

One also discovers the high-resolution aspect areas. Its materialization in translucent resin ture, and in addition to all this, the opportunity

when manipulating the printed object, where a leads us to perceive a constant play of solid to rethink the representation of the project. The

fine texture almost invisible to the naked eye, opacity and emptiness, depending on the an- next step will be to convert this method to ar-

but perceptible to the touch, subtly reveals the gle and scale of observation. It becomes some- chitecture, leaving aside the utopia of the com-

other theme of the project (Figg. 7, 8). how intangible, similar to some figural and pletely isolated object, and trying to reintegrate

The second object-field expresses the struc- dreamlike cloud formations (Damisch, 1972; all the constraints in this process. As the scope

tural flows as a source of information defining Figg. 7, 11). of the project will increase, the intermediate

the outer surface of the monolith. This time, Each of these four object-fields rests on a scales will definitely multiply, making it possible

the high-resolution system becomes essential base, a heavy block counterbalancing the light to deepen the micro-meso-macro trio and

in the definition of the project, where an algo- weight of the object placed on it. Although move towards the micro-meso(s)-macro. An

rithm will first decompose the total volume into completely white as an abstract volume, its exhaustive multi-resolution will then be imple-

a cluster of 1 mm voxels, which are three-di- upper surface is milled to express the intensity mented, creating true complexity on a variable

mensional pixels. Then, this collection of voxels of the field acting in the object, while reinter- scale, through the heterogeneous entangle-

is informed by the flows of the topological opti- preting, at another resolution, the system of ment of information layers.

152Puoi anche leggere